- Home

- Zachary Lipez

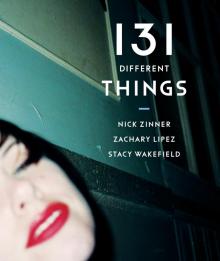

131 Different Things

131 Different Things Read online

Table of Contents

___________________

Ten Places We Had a Drink Together

Seven Bars, One Nightclub, One Loft & a Diner: 1

Eight Skinheads

Seven Bars, One Nightclub, One Loft & a Diner: 2

Eleven Moments on the Way to Somewhere Else

Seven Bars, One Nightclub, One Loft & a Diner: 3

Four Dogs, Two Cats & One Goat

Seven Bars, One Nightclub, One Loft & a Diner: 4

Eight Women in Their Apartments

Seven Bars, One Nightclub, One Loft & a Diner: 5

Fifteen Women Working at Night

Seven Bars, One Nightclub, One Loft & a Diner: 6

Eleven Guys

Seven Bars, One Nightclub, One Loft & a Diner: 1 (Again)

Six Bathrooms I Wanted to Remember

Seven Bars, One Nightclub, One Loft & a Diner: 7

Eleven People Doing Their Thing

Seven Happy Feelings

Seven Bars, One Nightclub, One Loft & a Diner: 8

Five Places I Went to Be Alone

Seven Bars, One Nightclub, One Loft & a Diner: 1 (Again)

Seven Salad Days

Seven Bars, One Nightclub, One Loft & a Diner: 9

Seven Times I Waited

Seven Bars, One Nightclub, One Loft & a Diner: 1 (Last Time)

Seven Moments of Clarity

Seven Bars, One Nightclub, One Loft & a Diner: 10

One Time We Got Back Together

About the Contributors

Copyright & Credits

About Akashic Books

ten

places

we had

a drink

together

1 New York 2004

2–3 berlin 2003

4 New York 1999

5–8 New York 2001

9 tokyo 2013

10 charleston, sc 1999

seven bars

one nightclub

one loft

& a diner

1

At 12:03 Saturday afternoon the phone in my pocket started vibrating. I didn’t need to pull it out to know it was the regulars calling because the gates to Pym’s Cup were still down. I was a block away. That was fine. They wouldn’t call the owner till twelve fifteen. They didn’t want to snitch on someone who had control of their noontime drink unless it was absolutely necessary.

When he saw me coming, Caldwell Teenager put down the receiver on the last working pay phone in the tristate area. He pulled a loosie out of the change dispenser and relit it. His hands trembled, but only a little.

“I just wanted to make sure you were okay. Are you okay?”

“I’m fine, Caldwell. Thank you.”

I undid the padlocks at each side of the gate, throwing them one by one in front of the entrance. Even though I didn’t need it, Caldwell helped me lift the gates.

The art on the wall was renewed on a regular basis. We’d had a dinosaur giving a cop the finger, a riot cop eating a cartoonish still-squealing BLT, I Miss Giuliani in sharp angular letters, and, of course, RIP . . . whatever. NYC, LES, Democracy. The current mural was Uncle Sam felating a skeletal camel with dollar signs dripping from his chin.

I put the book of skateboarding photography I’d been making a show of looking at on the train behind the register, cover peeking out. I glanced at my phone as I ran the dishwater to clean the glasses that the nighttime bartender had left. My phone, habitually dropped, was on its last legs, with nothing on the inside screen but Sanskrit, though the outer notifications told me that there were six missed calls that I’d failed to notice as I ran from the J/M/Z station. Caldwell Teenager (from the sidewalk pay phone, twice), Steve, Young Steve, Terry the Faggot, and Whitey. The other four must have gone to get coffee for their beers. They arrived en masse as I came out from the quixotic task of sort of cleaning the bathrooms.

“Any bodies in there?” Young Steve called out from the doorway.

Everyone laughed like it was the first time they’d heard that joke.

The regulars all drink beer at first, so I gave them all beer. I wiped down the bar with a damp rag. Someone put on the Monkees’ “Stepping Stone” three times in a row when I had my back turned. The regulars yelled at each other and no one fessed up and we all sang along for the third run.

There was change on the bar for my tips. I didn’t fling change off the bar till the evening.

Steve sat with Young Steve—who was a few years older than Steve but had been hanging out at Pym’s for a shorter time—in the corner by the lone large multipaned window. The panes were all different colors, replaced on the cheap as they got punched in. The sun managed to get through the cracks and graffiti and the Steves were convinced it made day drinking tropical. Whitey, a black Dominican born and bred on Avenue D, sat underneath the Absolutely No Card Playing sign that he, through bad luck and worse temper, had been the cause of. Caldwell Teenager, in his thirties looking fifty, stood next to him, leaning on the Addams Family pinball machine. Its top glass was cracked but it still worked, emitting the theme song every few minutes. In several hours these guys would sing along to that too. Terry the Faggot, not gay just not great at sticking up for himself, sat a little farther away, hunched in his trenchcoat, unsure if everyone was his friend today or not. I put half a shot of vodka in front of him. He’d been hassled pretty bad on my last shift. Everyone had taken ice cubes out of his rum and Coke to throw at him because he “didn’t really care much for Die Hard.” It was hard to defend. He always said shit like that. Just thinking about it, I wanted to take the vodka back.

At one thirty, my former wife came in. She was dragging some twentysomething coke vulture with her. She looked okay, half-Cuban/half-Irish and all that went with that (strikingly good looks till death, counterintuitively racist parents), but the dude with her was wearing a black leather jacket with, god help us all, no shirt underneath. It was thirty degrees outside. I poured myself a half pint.

“Good morning, Sam.”

Aviva hoisted an oversized black purse, fringed with silver studs and something clanging inside, onto the bar. She pushed it toward me. I put it behind the bar.

“I’ll have a margarita, no salt, extra ice, it’s early, and my boo here will have a beer. Do you care what kind, boo?”

“Whatever’s clever.”

I gave Aviva a look. She arched an eyebrow. I made her margarita weak.

Aviva managed the art factory for one of those ceramic monstrosity pop artists who didn’t disappear after the eighties, making sure the thirty passive-aggressive dudes she outranked painted enough silver circles and oversized ceramic doll parts to make the artist another twenty million.

When we’d gotten married, I still had a camera and was still naïve enough to think I had the talent to become the next Spike Jonze if Spike Jonze had quit or died before he made movies. Back then, Aviva was wild all the time and that was what I liked; she gave me action to document. But truth was, I was only dinking around; after some early success with my skateboarding shots, I never found another subject I could sink my teeth into, and when Aviva got bored of partying and focused on work, she turned out to have a lot of talent. She’d made a solid career, while I had given up trying. By the end, I was borrowing money from her all the time and resenting her for it. And when we broke up things only got worse. I didn’t even have a darkroom anymore and was too much of a curmudgeon to switch to digital. My only goal for my bartending career was to be like the ones in books or After Hours; the sort who didn’t hand out wisdom, didn’t flirt, but who grizzled regulars called “nurse.”

I gave her date—who looked like both the singer of the Dead Boys and a literal dead boy—a Bud Light. Fuck that

guy.

“Sam, this margarita is not your best. I’m not mad, as I’m not paying for it, but I think you should know.”

“Thank you, Aviva. I like your necklace.”

Aviva’s silver-and-turquoise multitiered chest piece descended into her bosom. She was leaning into the bar to accentuate it. I knew better than to think it was for my benefit. It was just the way she leaned into bars. She was five feet something, I guess plus-sized if we’re siding with the patriarchy. Hot by human standards, if no longer my type. She draped herself in layers of shawls and scarfs that always managed to shift off her shoulder and still stay on, held together by occult brooches and pins of German industrial bands. Her black hair was pulled high on the top and struggling to get free. I was thinking if she took the compliment well, and it seemed like things were okay, that I would show her my picture in the skateboarding book. I wanted to think she could still be proud of me.

“Do you know who got this necklace for me, Sam?”

“This guy?” I pointed to Stiv Shirtless, whose chin had fallen into his chest. Maybe on a nod, but maybe simply a coke-just-wore-off-no-sleep-and-now-it’s-the-afternoon prebrunch nap.

“No, Sam. You did. On our anniversary. Our first and only anniversary. You thought I didn’t notice that you’d forgotten, if you even ever knew the date, and you ran to some marked-up Tibet shop and bought me half a dozen necklaces. Did you even look at them?”

“I was just messing around. Of course I remember it. You look very nice.”

“Get fucked, Sam. I bought it last year on MacDougal. You gave me a bottle of Patrón. Then you disappeared up that slut’s cunt.”

“Ah.”

Aviva slammed down her empty glass and got up. She saw the photography book behind me and her tone softened: “Sorry if I’m snippy. I’ve been working sixty-

hour weeks at the studio. Now I have a few days off, what with the holiday weekend. I’m gonna work some stuff out. Deduct what I’d normally tip a human being from the money you owe me.”

“Will do. Thanks for coming by.”

She flipped me off and grabbed “boo” by the hair. He followed her out the bar bent over. I hoped their brunch would be overpriced.

It had been crazy to think she’d be interested in the book. I’d submitted my photos when we’d still been together. I liked to think I’d gotten in on my own, but I figured maybe she’d made some calls. I didn’t want to get into who owed what to who. I was pretty sure that ledger might sting. Whatever. I’d done plenty for her too. Plenty for lots of people. My friend Francis always said, “It’s not a favor if they expect gratitude.”

Everyone came to Pym’s prebrunch. A prebrunch drink gave you the courage to face the miserable staff and hungover crowds. It was less problematic than drinking at home before you went out to drink over twelve-dollar eggs.

I sipped a PBR. The long shift loomed ahead of me. I’d be here till eight if the swing-shift bartender showed, ten if he didn’t. I didn’t want him to. Money was tight and they’d just raised my Bushwick rent. I’d already been forced out of Williamsburg and, in counterintuitive order, Manhattan (which, before Vicki, I’d never thought I’d live in). I could use an extra fifty dollars. I didn’t mind the hours. A lot of bartenders got into it for short hours and fast money, but bartending wasn’t a stepping stone to something better for me. It was a calling of sorts, bellowing and insistent, in that I was good enough at it that I’d only get fired if I tried, or stole more than what I gave away or drank myself. And traditional third-round buybacks—while being phased out citywide because of high bar rent and just not enough patrons who deserved them—were not a firing offense in the places I worked. My boss screamed at us to not buy the regulars drinks but didn’t mean it in the slightest. Anyway, I’d been told that my dad had owned a bar in New Brunswick before I’d been born or, hell, maybe after I’d been born, so I figured it was in my thinning blood.

By four I had to ask both the Steves to leave. They were arguing about Iggy and the Stooges and playing “Raw Power” on repeat to bolster their positions on Bowie’s negative or positive influence. A good jukebox can ruin a bartender’s favorite bands. By play eight, I turned off the music, removed their drinks from the bar, and said, “See you tomorrow, gentlemen.” Eventually they stopped hurling obscenities and left, presumably to go three blocks east to the Library, where they refused to accept that they had been 86’d for at least a year. I had to return their $3.75 in tips but it was worth it. As soon as they left, Terry the Faggot stumbled over to the jukebox and played “Raw Power.”

The after-brunch crowd came in, a mixture of regulars, barely legal punks/skins trying on day drinking to see how it fit, and the inevitable slumming grad students, with their need to collect characters. We were a dive bar but a well-located one. Business was brisk. I worked fast, pouring drafts, laughing at mojito requests, showing people who called me “chief” the door. I answered to “man” and “yo.” Rules with low stakes are still rules.

I threw Whitey out at five for snoring too loud and Caldwell Teenager threw himself out when I walked in his direction after he grabbed a college girl’s ass. The first wave was replaced by the second. Murray and Drunk Fireman took over the regulars’ corner and ordered shots.

Sanita and Sarita came in at five thirty. They weren’t sisters but they could have been extras in the same version of Cleopatra. They were full-figured, big-boned, good to look at, with matching black Bettie Page bangs, heavy eyeliner, and lots of black lace. Murray and Drunk Fireman hooted when they came in. Drunk Fireman lumbered to the jukebox to play the Smiths to impress Sarita. I put up two strong vodka tonics with extra limes and minimal ice. Neither girl put any money down.

“Thanks, Saaaaaam,” Sanita and Sarita said in unison.

They vibed a couple smaller girls out of their barstools and got comfortable, building a fortress with their drinks and purses.

I was going to tell them that Aviva had been by but I thought better of it. Discussion of other females with Sanita and Sarita sometimes took a turn. They were Aviva fans for the most part, sometimes in ways that made me feel judged, but I made no pretense of understanding the friendships of women.

Sanita beat me to it: “So, Sam. We saw your lady.”

“Aviva? Not my lady. You girls are my ladies now, uh, ladies.”

“No, Sam. Your OTHER girl.”

My stomach did a thing. I looked to the bathroom out of habit. It would be disastrous to get sick. I had bad acid reflux to the point of social anxiety. My time spent in the bathroom was noted. I made people late for things. I made myself late worrying about making people late. Occasionally there was blood in the bowl. One of the reasons me and Francis, my best friend, bonded in high school was that he could get Nexium as well as pot back when you needed a prescription for the antacid and the idea of prescription pot was laughable. But taking a shit at Pym’s was out of the question. The bathroom doors had no locks. The owner had had them removed to facilitate the removal of fornicators and ODs.

I sweat a little from the forehead for a variety of reasons.

“Really.”

“Yep. Vicki. Large as life and twice as stuck up. Sorry. I mean super nice.” Sanita forced down a lime wedge with her straw. Sarita looked embarrassed and sent her smile in the direction of Drunk Fireman. He beamed at her.

Sanita snickered at the look on my face. “Oh, Sam. Calm down. I’m sorry I said anything. You have customers.”

Happy hour was in full swing. I ignored those waving money and served those trying to get my attention through force of will. I saw everyone, despite what they thought. There was a hierarchy based on customers’ grasp of etiquette.

The skinhead contingent was growing. That was a concern but not an issue yet. There were still plenty of other tough guys in the bar and the presence of Drunk Fireman, who was both enormous and a profound nonappreciator of subculture nuances, gave me comfort. Anyway, neither Flannery nor Big Timmy were there and they were the real proble

ms.

I wanted to get back to Sanita and Sarita and hear more. First Aviva coming through and now the mention of Vicki, my one true love, ender of marriages and my heart. My stomach wanted to do a Pee Wee Herman on the bar. (His dance from the movie, not the unjustly maligned jacking off.)

One of the skinheads, bless his dummy heart, distracted me by playing the one Skrewdriver song on the jukebox. It was on a mix CD that a former bartender had allowed when she was sleeping with one of the skins. It was from Skrewdriver’s first album, which was technically nonracist. But technically nonracist in skinhead terms just meant a wider range of peoples to hate and perform violence upon. I pressed the skip button hidden under the bar and yelled, “Someone must have bumped the machine!” There was shouting from the skins but laughter from Drunk Fireman and from Murray, who was friends with the owner and reputed to have killed a couple guys in the eighties, so that was that. I made kamikaze shots to placate all sides. Many tattooed hands were raised in cheers.

“Up with us, down with them.”

I collected tips off the bar and put them in the jar by the iron register. I rang some of the free-drink tips in to keep the ring up. I liked to ring at least a thousand per shift as a personal challenge. The old-fashioned register made a reassuring clang and bang that soothed my stomach. I turned back to Sanita and Sarita.

“I can’t handle games, Sanita. I’m fragile. Please say what you’re saying.”

“Sam. It was nothing. I shouldn’t have said anything. It’s just . . .”

She drew on her vodka tonic until it made a sucking noise. She giggled and held the glass out. Sarita did the same. I looked down their shirts. They owed me that much.

“We’ll tell you all about it when Francis gets here. He should hear this too. In the meantime, you have too many buttons buttoned.” Sanita leaned over the bar and unbuttoned my top two buttons and I let her. She tucked in my shirt, pausing for a second over my waist. Goth girls were particular about men and button-downs. One down was strictly Wall Street. All the way up you were a Nazi or a wizard. Three down you looked like a Bad Seed. Sanita had nice hands. I refilled their drinks.

131 Different Things

131 Different Things