- Home

- Zachary Lipez

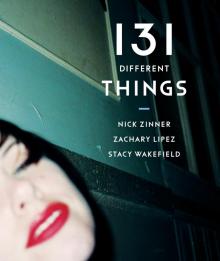

131 Different Things Page 4

131 Different Things Read online

Page 4

We were at the door when Seb appeared again like he was made of wind. I couldn’t stand behind Francis without looking comical. I shifted the book, as subtly as I could, to my left, above the waist, and held it like I was trying to staunch a wound.

“Are you leaving? Already?”

“We had a wonderful time,” Francis said. “I love your apartment. It’s exactly how I imagine heaven.”

Seb leaned in and we each accepted kisses to both cheeks. He wasn’t even gay or European. He just promoted parties.

“You know . . . it’s interesting, you showing up here. It’s very interesting. I mean, I always loved Vicki. She always made the most interesting choices, good or bad. Even when she was just a kid, showing up just to steal, like kids do, she was just so charming, what she chose to take. And you could tell, just by looking at her, that she was going to be so much more. And now she is! She is just so beautiful, now. You know, I don’t think that Vice or whatever could even do a cover without her now? You know? I just can’t envision that happening! She told me that there’s even a billboard on Houston coming. Coco in some jeans for god knows what, as if it matters. God, I hope I can see it from here. Even if I can’t, I’ll feel like I can. The way cool travels. That’s what Vicki’s eye just does. You must be so proud to have been with her.” He looked at me like I was part of the catering staff and my break was over.

Francis was quiet. He would have knocked this smartly dressed delicacy out if I had nodded. But instead I smiled. I wasn’t hiding the book anymore. I raised it to his face.

“Francis and I are borrowing this.”

“Take it. I have two.”

We picked up our shoes and, since putting them on would look like bowing, walked in our socks to the elevator. The walls seemed even cleaner than on our way in. I would have given anything for a Sharpie.

Francis said, “My favorite part was when you threatened the tiny man with Infinite Jest.”

“I think I won that party.” I tried to smile. I don’t think it showed.

Francis pulled a beer from inside his jacket and, as the elevator door opened, drank it down.

When the elevator arrived at the lobby, the doorman was standing there with his palm up to receive the stolen book. I put it in his hand without a word. Francis placed the empty bottle on top of the book and, taking me by the back of my shoulders, marched me out the door.

four dogs

two cats

& one goat

1 los angeles 2013

2 san diego 2016

3 nashville 2011

4 New York 2008

5 New York 2011

6 ho chi minh city 2016

7 brooklyn 1999

seven bars

one nightclub

one loft

& a diner

4

Before I moved out of the apartment I shared with Aviva in still vaguely industrial Williamsburg, when Vicki and I were deciding to stop just sleeping together wasted and try to have a relationship, I already had a lot of stuff in Vicki’s Manhattan apartment. I rarely slept at my South Williamsburg apartment because my wife was there, with our “roommate” who I strongly suspected rarely slept in his own room. I wasn’t in any position to judge, but I did.

My stuff started out, as these accumulations do, as a T-shirt Vicki borrowed so that she could sleep in it after we fucked. That became a T-shirt and a pair of pants that I spilled something on, or she bled on, so I had to leave them there. I’d borrowed some pants that had been lying around in the back of one of her drawers. I assumed they were previously Flannery’s, but it wouldn’t have been polite to ask. So the original pants stayed, with the original shirt, and eventually they were joined by jackets and more shirts: Supertouch, Sheer Terror, a few Fred Perrys. I may have usurped a few of Flannery’s Fred Perrys too. The way I saw it, Flannery’s loss was so huge and my gain so enormous that any attrition of clothing was the least of his problems and the least of my joy. And we were the same size, at the time. He’d since grown.

Anyway, single socks became pairs of socks that became shoes that became everything that I valued enough to not leave alone at my own apartment with my wife, the “roommate,” and my wife’s righteous and tactile rage. My wife wasn’t averse to the cliché of throwing a cheating spouse’s shit out the window. That’s what the window was for. My wife and I lived above a bar where was a lot of foot traffic. I still see guys walking around in band T-shirts that I’m positive were once mine. In this way the redistribution of wealth is achieved, and in this way my wardrobe and comic book collection and my body and self became residents of Vicki’s apartment, which, as luck would have it, was also situated above a bar. Since Vicki never complained, I assumed that my moving in was what she wanted. Living with Aviva had been hard, a constant negotiation of space and needs. We cried a lot even when things were great. She’d push me to explain things I only said as jokes, or she’d make me watch a documentary on Marc Rothko when I wanted to see River’s Edge again. She’d ask how many pictures I’d taken that day. When was I going to switch to digital? Living with Vicki was easier. Vicki and I never cried and when we watched movies, she’d pick and then I’d watch her watch them. I’d laugh when she laughed, which was often. And Vicki didn’t bother me about how many pictures I took. She was busy taking her own.

Living above a bar was pretty common in the circles we (me, Francis, Aviva, Vicki, etc.) ran in. It’s cheaper to live above a bar and there are a lot of bars. We (me, Aviva, Vicki, etc.) were not the sort of people who complained about the noise. Instead, as our neighborhoods descended into yuppified tedium, the bars below complained about us; our disrupting of trivia nights, poetry slams, and speed-dating happy hours with our slamming of furniture, exaggerated coitus, and clothes raining down from the second-story window.

Vicki (and then Vicki and I), however, lived above a bar we liked, Odell’s, and it liked us back. We were happy to have a place where we could drink cheap and slowly at, before I had to go to work and she had to go out drinking, which was also work, both in who she had to glad-hand and in how she, at the time, drank. The owner of Odell’s was happy to have two lovebirds in the window, playing pool at four in the afternoon. He let Vicki hang her photos on the wall and they let me brag about how I was the one who put the nails in.

Odell’s was owned by an elderly black Korean man who didn’t allow swearing but turned a blind eye to the gaggle of coke dealers by the bathroom doors. Odell’s, being on 3rd and C, was one of the last spots where a dive bar could eke out an existence into the mid-aughts. Then Vicki and I weren’t living together and, for unrelated reasons, Odell went to Florida.

Odell’s became the Ironweed, still a dive bar by 2006 East Village standards; meaning by décor alone, with six-dollar Budweiser and nine-dollar Jameson. The crowd was older skinheads turned drug dealers, and thirtysomething hardcore guys who’d done some time but were now doing okay. It was basically a cop bar, but with no cops. Just the sons of cops and firemen gone to seed.

The culture of aging New York City skinheads is a hard one to wrap one’s head around and most people don’t try. For former New Jersey punks such as me and Francis, it was important to parse the delicate social webbing. And serving and drinking with these mooks required a certain amount of connoisseurship. Bascially: in the eighties god created hardcore and CBGBs matinee shows. He also invented drug dealing as a way to escape either the endemic poverty of the ghetto or the drudgery of lower-middle-class outer-borough shitheelery. There was a lot of overlap of hip-hop and white guys in Adidas tracksuits that I never quite understood, but the gist was that what had started as teenage youth crews evolved into actual white (with a sprinkling of Puerto Rican and black) ganghood. Without all the usual racist skinhead connotations but plenty of the violence. As these guys aged, the gang aspects diminished, but the brotherhoods remained. Francis, having played bass in plenty of minor Jersey tough-guy hardcore bands, was free and easy with these guys, but I—maybe because I always sided with the gi

rlfriends in disputes; or maybe, as it was once pointed out by a gakked-out bruiser, just because of my “pussy eyes”—was still seen as a wimp. And that was from the guys who didn’t even like Flannery. Flannery’s crew straight up hated me. Especially his number two, Big Timmy. If I’d been invisible before Vicki, I was now communism, AIDS, and whatever make and model killed Ian Stewart afterward.

Having Big Timmy hate you was scarier than having Flannery hate you. Big Timmy did terrible things to large men and still wasn’t 86’d from anywhere. I couldn’t think of a greater testament to his legend. I’d seen him walk up to bouncers who just the week before had to drag him out of a place, five on one. He’d shake their hands like, Well, you know how it goes, god didn’t invent emergency rooms not for nothing. And they’d let him back on in. What else could they do? I’d watch the bouncers shrug helplessly at their managers. You want him out? their look said. You do it.

The Ironweed, besides sitting in the place of such fraught Vicki-and-Sam history, was also where Francis’s number one ex-girlfriend, Vicki’s on-again-off-again best friend, Sara Seventeen worked. Sara got her name from when she worked at the American Apparel on Houston, where, along with a store culture that seemed to run entirely on MDMA and the possession of fake IDs rendered irrelevant by the serial dating of older Lower East Side bar staff, there were two other Saras. Usually, if you forget a girl’s name, safe bets are Sara(h) or Kate. One Sara was seventeen, one was eighteen, and one, the American Apparel elder, was nineteen. Like so many New York nicknames, the names stuck even though Sara Seventeen was now twenty-three.

Vicki had been Sara’s best friend since they were teenagers and just beginning to get older Queens punks and construction workers to buy them wine and tequila. When Sara was twenty, she and Francis had a torrid affair, or what would be considered by most an affair. For Francis and Sara Seventeen, a week was a long-term relationship.

The Ironweed was two long rooms, both with stained wood–paneled walls that could almost be called brindle. They were graffiti free. Tagging was a serious no-no. Even if the clientele had no shortage of former taggers, that shit was for other people’s clubhouses. The first room, where the serving bar was, had the requisite deejay booth, where you could harass the deejay for not playing vinyl or, if he/she was, jump up and down to make the needle skip. There were a couple mirrors, strategically placed out of punching range behind the deejay booth and the bar. The back room still had a pool table, for fights and quarter stealing. Dimly lit booths surrounded the table, and beyond the booths there was the long line to the bathroom.

The moment we shoved our way through the crowd to get to the bar, the Upsetters’ “Drugs and Poison” was blaring from ceiling-mounted speakers. There was a smattering of women in Trash and Vaudeville punk and rockabilly dresses, but Vicki had been phasing out the Stop Staring! look even when we first hooked up. Yet I was still a breathless wreck with every small-boned baby-doll dress that moved within my periphery.

Sara had a smile that was warm and wry. “Francis! You look terrible. You said you were coming by, but I assumed you were lying. As you do.”

“Sara, you look beautiful. Like our sex tape come to life.”

“I taped over our sex tape. Critics found my acting unconvincing.”

“Then they never heard you say, I love you.”

Francis leaned over the bar and gave Sara a kiss. She brushed her black hair from the side of her neck to accept it. Francis lingered. Sara looked at me.

“Hi, Sam. Looking for Vicki? I think she’s still here, but honestly, I’ve been fucking slammed.” She held up a finger of warning to Francis and he kept whatever joke he had in the offing to himself. She continued, “She may be in the back. She never says bye when she leaves.”

The bar was two people deep to get drinks. The barback looked harried. The crowd was 70 percent men, with the females mainly sitting on laps or firmly protected in circles of glowering, tattooed strongmen. On these guys, tattoos still looked like warnings. Francis and I had shared history with most of these men. Respect was given to those who had been serving drinks through the rapid changes to the neighborhood. Some, the ones who liked wiseasses and didn’t take free drinks for granted, even liked us. These guys would smile, giving their pals permission to nod. We shook hands with everyone, made hard eye contact, showed respect. Francis, like I said, was more comfortable, but even he knew that booze mixed with limited female presence mixed with our way of talking—which could easily be taken, correctly or not, as condescension—might result in serious bodily harm. I could never remember how long I was supposed to maintain eye contact, so I looked at my drink a lot.

Francis and I worked our way to the back. I didn’t see Vicki anywhere but I didn’t really see much. Even though smoking had been outlawed in bars three years ago, after midnight the back room would fill with cigarette smoke. Along with the lighting, it was difficult to place faces until they were within kissing distance. Once upon a time that had been appealing. In a different crowd, Francis would be leaning in on everyone, taking cigarettes out of mouths to take a quick puff before placing them back into lips. But here he kept his hands to himself. He got engrossed in conversation with a baldhead in a dark-blue Fred Perry. Vicki wasn’t here. I slouched into the bathroom line. I stared into my beer and waited to piss. I was feeling queasy but no way in hell was I going to do more than that in those bathrooms.

Peeing allowed me to consider the future. Exiting the bathroom, still anxious, I repeated various phrases I’d say to Vicki when I found her, what she’d say back to me, what I’d say back with a crooked smile, working that charm to remind her of what I knew she was missing. It was a ten-second reverie coupled with my staring at the fractal crack of my flip-phone. I could get nothing from the device and willing it to ring from that future was not working.

Then I got hit. The dumb vacancy got smacked right off me, a large open hand knocking the color from my face, replacing it with a new color.

I dropped my phone and my beer. Both shattered. I put my hand to my face. It was shoved into me by another slap. Flannery was really strong and had momentum heading into the men’s room as I was coming out. Having smacked me twice, he didn’t even bother to move. He didn’t have to. Nobody breaks up a slap fight. And no one knows how to respond to one either. I sure didn’t. My fists clenched, but if I threw a punch, he was going to seriously fuck me up. I’d been hit enough that I could control my instinct to tear up, but it hurt, and I was feeling the embarrassment more than the pain. Everyone around us was. Some tough guys, who didn’t run with crews as big as Flannery’s, looked at me and then looked down.

Francis appeared by my side, and stood there looking warily at Flannery, who was grinning like a little boy who just learned to spit.

“I just fucking slapped your bitch, Francis. Like the fucking bitch he is. What do you think? You interested in doing something about it? Hit me with your purse?”

“I’m good.”

“You’re good? You’re fucking good? You sure? I mean, there’s two of you and only one of me so, if you aren’t sure that you’re good, fucking say something while I’m here, man to man, and don’t back down like a pussy and make fucking jokes when I leave. I know what a funny fucking guy you are, Francis.”

“I’m good. So is Sam. We’re both good. Just looking for someone.”

“I know who you’re fucking looking for, why do you think I fucking smacked this faggot? That, and he isn’t worth me closing my fist, I mean. I don’t close my fists for queers. That’s fucking prejudiced.”

I was too humiliated to come up with anything to say, and for some reason I held out my hand. He gave my hand a look one would give something weak and diseased.

“Francis, I think maybe it would be for the best if you took your queer little buddy out of here. And I don’t mean queer in the faggot sense, but in the I’m-going-to-fucking-end-his-piece-of-shit-pussy-life sense. He fooled Vicki, but he never fooled me. You can’t fool me. I am truth.�

��

An interesting observation. I had to agree. He felt like a very true thing when he hit your face with his hand. People too often forget what truth is until the Flannerys of the world remind them.

My face was bleeding. Francis walked me to the front of the bar and people parted like they didn’t want to catch what I had.

The deejay put on “Somebody’s Gonna Get Their Head Kicked in Tonight.” When we got to the bar, Sara Seventeen said, “If it’s any consolation, Sam, he couldn’t protect me for shit either.”

I was relieved that her contempt for Francis trumped all.

Francis looked hurt. “Fuck you, Sara! It was open hand!”

We pushed our way out onto the street. Francis lit a cigarette for me. When I took a drag my gums stung. All of a sudden I wanted to hit everything.

A group of youths passed by and I hated the gloss of their hair, the cut of their jeans, their young, high, happy voices. The airbrush job on the back of one their leather jackets, a neon hodgepodge of Nic Cage crucified on a cross, surrounded by angels, pushed me over the edge.

“What does your jacket mean?! It’s just dumb! I hope everyone at NYU gets fucking cancer and you die!”

My spittle landed near their shoes. They didn’t look impressed.

Francis put his hand up. “Sorry. He just lost a fight. Keep walking. You fuckers I can take.”

The boys allowed themselves to be pulled down the block by their girlfriends in gold hoop earrings and streetwear. They were still giving us the finger and calling us old as they turned the corner.

I turned on Francis. “Fuck you, dude! Fuck you! What happened in there? What just fucking happened? I hate you!”

“Sam, I swear, if he ever hits you with a closed fist . . .”

“That’s not a real thing, Francis! I mean . . . it is! But! I would have stuck up for you.”

“First of all, Sam, maybe you would have. Second of all, I’m really sorry. Live to fight another day, my friend. And the main thing is finding Vicki, yes? Yes?” Francis looked at me with eyes that had crashed a million pairs of panties.

131 Different Things

131 Different Things